It’s Women’s Month, and we are continuing the conversation about gender bias in medical research. The lack of inclusion and understanding of women in medicine has important, and sometimes fatal, effects on women’s health.

Gender bias in medical research permeates the healthcare system, from research to diagnosis and treatment. A major problem is the lack of representation in research, which causes serious problems in diagnosis and treatment for women.

In this blog, we discuss this issue and look at solutions proposed by experts.

Lack of representation in research

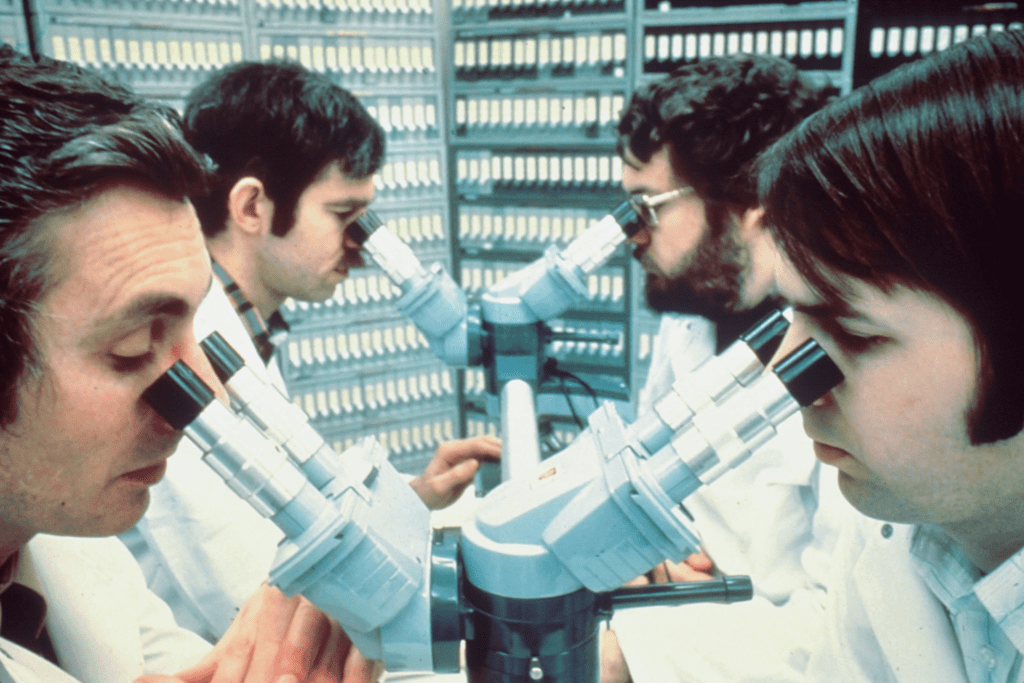

An important consequence of gender bias is that men mostly conduct medical research.

Why is this? Historically, scientists believed that men, lacking menstrual cycles and the possibility of pregnancy, were better test subjects. As a result, medical trials systematically excluded women for a long time. Instead, medical science was studying mostly male cells, animals, and humans. Researchers justified excluding female animals because they caused too much variability in results. However, a 2010 study of sex bias in mammal research has found this explanation to be “without foundation”.

For example, Rockefeller University conducted a pilot study backed by National Institutes of Health. Despite looking at obesity’s impact on breast and uterine cancer, the study doesn’t include a single woman, according to Maya Dusenbery’s 2018 novel Doing Harm.

In the last 50 years we see more women in human studies, but increasing male bias in non-human studies. Still today, more men participate in medical trials than women. Even in studies of both sexes, not all drug researchers consider sex or gender when analyzing results.

Why gender bias in research matters

Why does this matter?

It’s not just a question of equal representation. There are notable differences between the male and female body which change the way diseases, drugs, and therapies affect people.

Some medical research results can be extrapolated between sexes. However hormones affect many pathways, such as cardiovascular disease and some cancers, which differ significantly between sexes.

Because of this, many pre-90s studies are flawed and doctors have a poorer understanding of female and intersex people’s health. This also means the drugs that come out of these studies are less safe and effective for women because of their exclusion from the development process. To illustrate, the US FDA withdrew eight drugs with unacceptable risks for women between 1997 and 2001.

The lack of female representation in research also complicates diagnosis. Researchers often understudy diseases that affect mostly women, and as a result doctors often undertreat, misdiagnose, or undiagnose these diseases. For example, some say that waiting to have children can cause endometriosis while getting pregnant can cure it. This was also said about breast cancer before it was proven otherwise.

Progress in research

The mystery around women’s illnesses has a great impact on women’s health. Luckily, there are advocates in the field taking steps to improve women’s health research and treatment.

In the 80s, US female scientists set out to create what is now known as the Society for Women’s Health Research to advocate for better health research in women.

Ongoing advocacy from groups like this one has incited important regulatory changes. In 1993 the FDA and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) made it obligatory to include women in clinical trials. 20 years ago, the NIH mandated that every study they fund must disclose the proportions of women and minorities included. If these groups were not included, researchers had to provide reasoning.

Despite this progress, many grants with few or no women are still funded.

Solutions to gender bias in research

What can be done?

An important step is education and awareness. Healthcare professionals and those they serve need to understand gender bias, how we all hold these biases, and how they impact healthcare.

An American Medical Association (AMA) article suggests nourishing education with research and workforce development. The goal would be to show how it’s possible to integrate sex and gender into basic science and clinical research platforms. They also advocate for sponsorship, including how to discuss sex and gender in medical research and journals.

Concretely, there must be more sex and gender diversity in research. Women currently reflect about 50% of participants in NIH-supported clinical research. However, the same does not apply for all studies, nor does it erase decades of male-only research.

We’re calling on health organizations and researchers to prioritize gender diversity in relevant studies and fund research to fill knowledge gaps.

If we want to ensure women’s health, we must not only include them in research, but design research specifically for their bodies.

Discover more related blogs from Dr. Tanya Williams Fertility Centre:

The Hidden Struggles of Black Women with Infertility: Three Women’s Stories